In the recently released Privacy Act Review Report, the Attorney-General’s Department makes numerous important proposals that could see the legislation, enacted in 1988, begin to catch up to leading privacy laws globally.

Among the positive proposed changes are: more realistic definitions of personal information and consent, tighter limits on data retention, a right to erasure, and a requirement for data practices to be fair and reasonable.

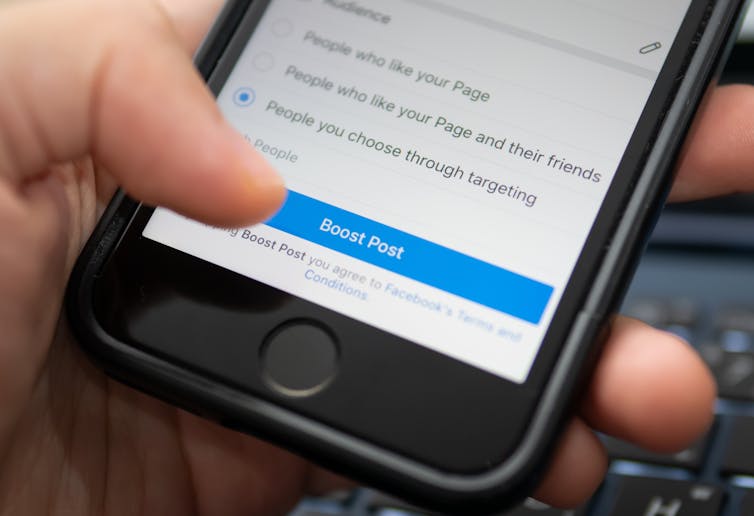

However, the report’s proposals on targeted advertising don’t properly address the power imbalance between companies and consumers. Instead, they largely accept a status quo that sacrifices consumer privacy to the demands of online targeted ad businesses.

Capturing personal information used to track and profile

Obligations under the existing Privacy Act only apply to “personal information”, but there has been legal uncertainty about what exactly constitutes “personal information”.

Currently, companies can track an individual’s online behaviour across different websites and connect it with their offline movements by matching their data with data collected from third parties, such as retailers or data brokers.

Some of these companies claim they’re not dealing in “personal information” since they don’t use the individual’s name or email address. Instead, the matching is done based on a unique identifier allocated to that person – such as a hashed email, for example.

The report proposes an expanded definition of “personal information” that clearly includes the various technical and online identifiers being used to track and profile consumers. Under this definition, companies could no longer claim such data collection and sharing are outside the scope of the Privacy Act.

Improved consent (when required)

The report also proposes higher standards for how consent is sought, in cases where the act requires it. This would require voluntary, informed, current, specific and unambiguous consent.

This would work against organisations claiming consumers have consented to unexpected data uses just because they used a website or an app with a link to a broadly worded privacy policy with take-it-or-leave-it terms.

For example, companies would need to demonstrate the higher standard of consent to collect sensitive information about someone’s mental health or sexual orientation. The report also proposes that some further data practices, such as precise geolocation tracking, should require consent.

However, it specifically states consent should not be required for some targeted ad practices. Yet surveys show most consumers regard these as misuses of their personal information.

‘Fair and reasonable’ data practices

The report proposes a “fair and reasonable” test for dealings with personal information in general.

This recognises that consumers are saddled with too much of the responsibility for managing how their personal information is collected and used, while they lack the information, resources, expertise and control to do this effectively.

Instead, organisations covered by the Privacy Act should ensure their data handling practices are “fair and reasonable”, regardless of whether they have consumer consent. This would include considering whether a reasonable person would expect the data to be collected, used or disclosed in that way, and whether any dealing with children’s information is in the best interests of the child.

Prohibiting targeted ads based on sensitive information

The report proposes the prohibition of targeting based on sensitive information and traits. However, it’s not always easy to draw the line between “sensitive” information or traits, and other personal information.

For instance, is having an interest in “cosmetic procedures” or “rapid weight loss” a sensitive trait, or a general reading interest? Companies may exploit such grey areas. So while prohibiting targeting based on sensitive information is appropriate, it’s not enough in itself.

Another loophole arises in the report’s proposal that consumer consent should be necessary before an organisation trades in their personal information. The report leaves open an exception to this consent requirement where the “trading” is reasonably necessary for an organisation’s functions or activities.

This may be a substantial exception: data brokers, for example, might argue their trade in personal information (without consumers’ knowledge or consent) is necessary.

Opt out only, not opt in

Both the ACCC and the UK Competition & Markets Authority have recommended consumers should opt in to the use of their personal information for targeted advertising if they wish to see this content.

But the report proposes individuals should only be allowed to opt out of “seeing” targeted ads. This still wouldn’t stop companies from collecting, using and disclosing a user’s personal information for broader targeting purposes.

Even if a consumer opts out of seeing targeted ads, a business may continue to collect their personal information to create “lookalike audiences” and target other people with similar attributes.

Although having the option to opt out of seeing targeted ads gives consumers some limited control, companies still control the “choice architecture” of such settings. They can use their control to make opting out confusing and difficult for users, by forcing them to navigate through multiple pages or websites with obscurely labelled settings.

Are targeted ads necessary to support online services?

This limitation of consumers’ choices was partly explained by the view of the Attorney-General’s Department that targeted ads are necessary to fund “free” services. This refers to services where consumers “pay” with their attention and data (which companies use to make revenue from targeted advertising).

However, many companies using customers’ personal information for targeted ad businesses aren’t providing free services. Consider online marketplaces such as Amazon or eBay, or subscription-based products of media companies such as NewsCorp and Nine.

Meta (Facebook) and the Interactive Advertising Bureau Australia argued that if consumers opt out of targeted ads, a company should be able to stop offering them the service in question. This proposal was rejected on the basis that a platform can still show non-targeted ads to such consumers.

Inconsistently, the report failed to question broader claims that targeted advertising – as opposed to less intrusive forms of advertising – must be protected for online services to be viable.

Real change is needed

The reform of our privacy laws is long overdue. The government should avoid watering down potential improvements by attempting to preserve the status quo dictated by large businesses.

The government is seeking feedback on the report until March 31. It will then decide on the final form of the reforms it proposes, before these are debated in Parliament. ![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.