Katharine Kemp, Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Law, UNSW, and Co-Leader, ‘Data as a Source of Market Power’ Research Stream of The Allens Hub for Technology, Law and Innovation, UNSW

Australia’s consumer watchdog has recommended major changes to our consumer protection and privacy laws. If these reforms are adopted, consumers will have much more say about how we deal with Google, Facebook, and other businesses.

The proposals include a right to request erasure of our information; choices about whether we are tracked online and offline; potential penalties of A$10 million or more for companies that misuse our information or impose unfair privacy terms; and default settings that favour privacy.

The report from the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) says consumers have growing concerns about the often invisible ways companies track us and disclose our information to third parties. At the same time, many consumers find privacy policies almost impossible to understand and feel they have no choice but to accept.

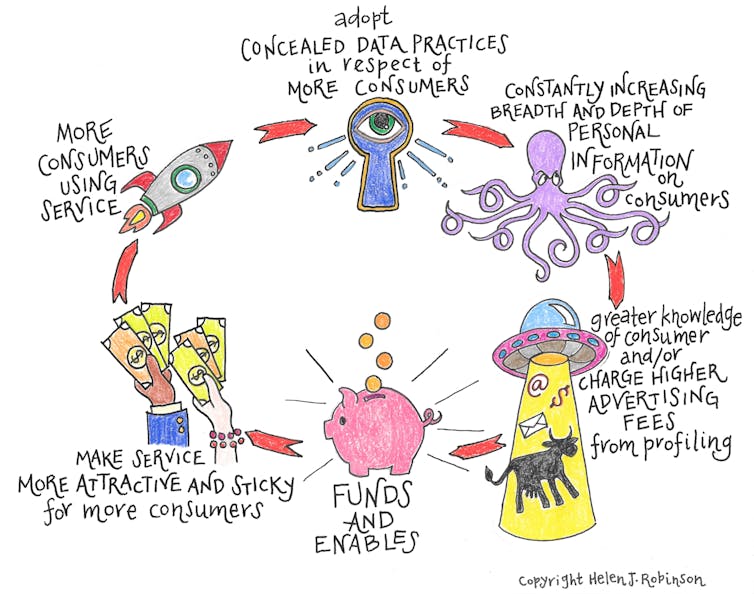

My latest research paper details how companies that trade in our personal data have incentives to conceal their true practices, so they can use vast quantities of data about us for profit without pushback from consumers. This can preserve companies’ market power, cause harm to consumers, and make it harder for other companies to compete on improved privacy.

Privacy policies are broken

The ACCC report points out that privacy policies tend to be long, complex, hard to navigate, and often create obstacles to opting out of intrusive practices. Many of them are not informing consumers about what actually happens to their information or providing real choices.

Many consumers are unaware, for example, that Facebook can track their activity online when they are logged out, or even if they are not a Facebook user.

Some privacy policies are outright misleading. Last month, the US Federal Trade Commission settled with Facebook on a US$5 billion fine as a penalty for repeatedly misleading users about the fact that personal information could be accessed by third-party apps without the user’s consent, if a user’s Facebook “friend” gave consent.If this fine sounds large, bear in mind that Facebook’s share price went up after the FTC approved the settlement.

The ACCC is now investigating privacy representations by Google and Facebook under the Australian Consumer Law, and has taken action against the medical appointment booking app Health Engine for allegedly misleading patients while it was selling their information to insurance brokers.

Nothing to hide…?

Consumers generally have very little idea about what information about them is actually collected online or disclosed to other companies, and how that can work to their disadvantage.

A recent report by the Consumer Policy Research Centre explained how companies most of us have never heard of – data aggregators, data brokers, data analysts, and so on – are trading in our personal information. These companies often collect thousands of data points on individuals from various companies we deal with, and use them to provide information about us to companies and political parties.

Data companies have sorted consumers into lists on the basis of sensitive details about their lifestyles, personal politics and even medical conditions, as revealed by reports by the ACCC and the US Federal Trade Commission. Say you’re a keen jogger, worried about your cholesterol, with broadly progressive political views and a particular interest in climate change – data companies know all this about you and much more besides.

So what, you might ask. If you’ve nothing to hide, you’ve nothing to lose, right? Not so. The more our personal information is collected, stored and disclosed to new parties, the more our risk of harm increases.

Potential harms include fraud and identity theft (suffered by 1 in 10 Australians); being charged higher retail prices, insurance premiums or interest rates on the basis of our online behaviour; and having our information combined with information from other sources to reveal intimate details about our health, financial status, relationships, political views, and even sexual activity.

In written testimony to the US House of Representatives, legal scholar Frank Pasquale explained that data brokers have created lists of sexual assault victims, people with sexually transmitted diseases, Alzheimer’s, dementia, AIDS, sexual impotence or depression. There are also lists of “impulse buyers”, and lists of people who are known to be susceptible to particular types of advertising.

Major upgrades to Australian privacy laws

According to the ACCC, Australia’s privacy law is not protecting us from these harms, and falls well behind privacy protections consumers enjoy in comparable countries in the European Union, for example. This is bad for business too, because weak privacy protection undermines consumer trust.

Importantly, the ACCC’s proposed changes wouldn’t just apply to Google and Facebook, but to all companies governed by the Privacy Act, including retail and airline loyalty rewards schemes, media companies, and online marketplaces such as Amazon and eBay.

Australia’s privacy legislation (and most privacy policies) only protect our “personal information”. The ACCC says the definition of “personal information” needs to be clarified to include technical data like our IP addresses and device identifiers, which can be far more accurate in identifying us than our names or contact details.

Whereas some companies currently keep our information for long periods, the ACCC says we should have a right to request erasure to limit the risks of harm, including from major data breaches and reidentification of anonymised data.

Companies should stop pre-ticking boxes in favour of intrusive practices such as location tracking and profiling. Default settings should favour privacy.

Currently, there is no law against “serious invasions of privacy” in Australia, and the Privacy Act gives individuals no direct right of action. According to the ACCC, this should change. It also supports plans to increase maximum corporate penalties under the Privacy Act from A$2.1 million to A$10 million (or 10% of turnover or three times the benefit, whichever is larger).

Increased deterrence from consumer protection laws

Our unfair contract terms law could be used to attack unfair terms imposed by privacy policies. The problem is, currently, this only means we can draw a line through unfair terms. The law should be amended to make unfair terms illegal and impose potential fines of A$10 million or more.

The ACCC also recommends Australia adopt a new law against “unfair trading practices”, similar to those used in other countries to tackle corporate wrongdoing including inadequate data security and exploitative terms of use.

So far, the government has acknowledged that reforms are needed but has not committed to making the recommended changes. The government’s 12-week consultation period on the recommendations ends on October 24, with submissions due by September 12.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.